‘I’m hoping there will be an equal playing field’: The ongoing fight for equity

Rere Akinyemi enjoys the AAP program at Carson but wants it to do more for disadvantaged students. Photo credit: Rere Akinyemi

Ahmaud Arbery. Rayshard Brooks. Breonna Taylor. Jacob Blake. George Floyd. Thanks to a year rife with incidents of police brutality, these ordinary people became household names.

The outrage that followed their shootings and/or deaths has sparked conversations in the Carson community and the broader world not just about police brutality and implicit bias, but also about the issues of underrepresentation in the education sector, which has often played a part in systemic racism and is seen as a pipeline to poverty and a lack of economic mobility.

That broader discussion includes an examination of equity in Fairfax County Public Schools’ AAP program. as well as a new proposal to even out the playing field for applicants at Thomas Jefferson High School.

‘Good Progress but Challenges Remain’

On May 5, 2020, in the middle of pandemic that challenged all teachers and exacerbated racial and economic education gaps, professors from the University of Virginia and three other universities released a sort of audit on the state of equity in AAP titled “Good Progress but Challenges Remain: Achieving Equity in Fairfax County Public Schools Advanced Academic Programs.”

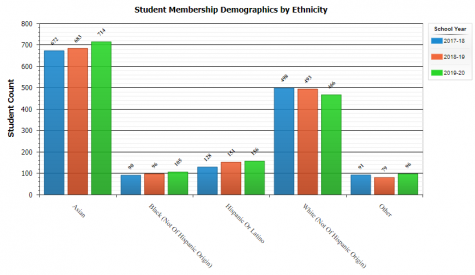

Among the most interesting finds? Asian-Americans were roughly 19% of the students that took the NNAT and COGAT for admission into the Advanced Academic Program (the cohort), but nearly 31% of the students screened (“in-pool”) for the final cut. Meanwhile, Hispanic and African-American students made up around 25% and 10% of the test-takers respectively, but only made up 11% and 6% of the screened pool. Those are two groups that have been traditionally held behind and shut out of higher education as a result of systemic racism.

This, the report says, “is a clear illustration of the disproportional enrollment/equity challenges that are common to the AAP program in FCPS . . . Students from African American and Hispanic families are disproportionally underrepresented both in the screening pool as well as among those deemed Level IV eligible.”

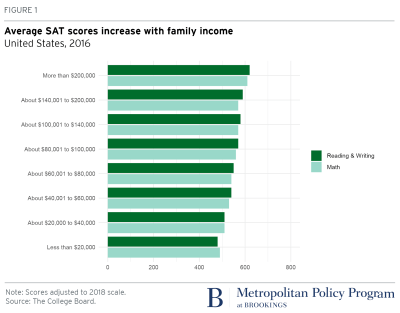

The assessment of the program posits one likely reason for this discrepancy: race and economic status are often tied together, and, for the most part, standardized tests assess your family’s wealth more than they do your intelligence.

How does that affect Carson, one of the largest AAP middle school centers in all of FCPS? What does this long-standing educational inequality mean in an age where police brutality targets these under-represented groups disproportionately, and where these groups are the hardest hit by the novel coronavirus pandemic?

‘There is an equity issue’

Mrs. Carrie Guild, a seventh-grade history teacher, thinks the answer is clear: “[It’s] very apparent. There is an equity issue.”

Mrs. Guild has also taught in schools in the eastern part of the county, where some schools struggle with a lack of funding, due to relatively lower house-hold incomes in the surrounding areas and less collected in property taxes (where schools get a good bit of their money from).

“[At] certain schools, kids do have more opportunities, and the make-up of the school is different.”

Mr. Moosa Shah, a seventh-grade science teacher, agrees.

“Rachel Carson’s AAP classes are pretty diverse with students from many backgrounds. However, the percentages of African American, Latino/Hispanic, and Middle Eastern students are much lower in comparison to other groups.”

Carson students who are of African-American, Latino, or Hispanic make up just 17% of the student body combined. That percentage in FCPS overall is closer to 37%.

Even with the apparent inequalities, Rere Akinyemi, an eighth-grader at Carson, enjoys AAP a lot.

“[AAP] challenges me,” she said. “It makes me work harder.”

However, she says, “Definitely in elementary school, [at Oak Hill Elementary] there were times when I realized that as a first-generation African-American, a lot of my friends in AAP came from different backgrounds than me. It’s not a big thing, though.”

Diversity in Carson moving forward

Mr. Shah would like to see more inclusion and equity in AAP and Carson.

“Everyone benefits from diversity,” he says. “We are richer and grow so much more when we are diverse in cultures, backgrounds, experiences, ideology, depth of knowledge, etc. The more young students work together with people from all backgrounds, both cultural and socioeconomic, the more empathetic, caring, and sensitive they become.”

Mrs. Guild concurs.

“A lot of disadvantaged kids aren’t given those [STEM] opportunities . . . kids who aren’t exposed don’t know that they might have interest in STEM. [Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology] might not be for everyone, but it could be for them.”

Rere has a slightly different look on the situation.

“Of course everything could be more racially diverse,” Rere says. But, she cautions, “in America, sometimes people use race as an excuse. We have to make sure that parents and teachers and everybody are telling those kids that they can be great, and instill good values in them, because a lot of times the resources are there. You have to go out and look at them.”

Also things that should be on the bucket list to close the gap? Mrs. Guild says, “Talking about inequity and bringing it to the forefront right now helps. Communicating and giving opportunities helps.”

Mr. Shah also had ideas for how to mitigate educational inequity for everyone.

“Affordable and high level preschool will make a difference,” he says. “Access to technology, books, opportunities should start as early as possible. Not only access for students, but for parents and grandparents. Families who are immigrants and may not know the American educational system should be provided easy to access advocates to help them maneuver all the opportunities out there.”

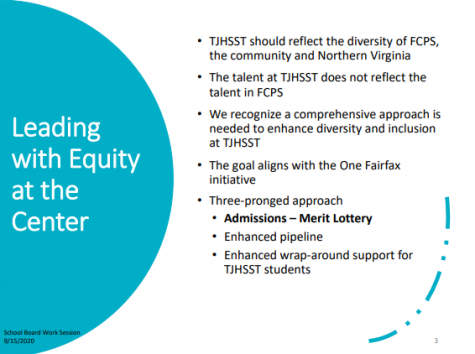

In fact, FCPS’s new proposal for TJ admissions seems to take the idea of providing opportunity to people who for too long have not gotten it to heart. On Sept. 15, 2020, School Board members at a work session considered a proposal of a “merit lottery,” where applicants who meet different criteria are entered into a randomized lottery system that restricts the amount of students from the different regions TJ pulls from. It may be adopted, over many current TJ parents’ objections.

And it’s not just TJ that’s changing. The report does point out that progress has been made and that lots of school systems do advanced education worse. However, Mrs. Guild believes that that’s not good enough.

“I’m hoping there will be an equal playing field. I want people to help each other out,” she says.

Mr. Shah, too, wants a world where everyone helps each other.

“In a world where you can be anything,” he says, “be kind.”

Vishwa Rakasi is a seventh-grader on Legacy. In his spare time, he dabbles in screenwriting, regular writing, poetry, and competitive swimming. His favorite...